Use Oplop for your web site passwords

The Gawker breach made mainstream what’s been known for a while: we don’t use good passwords, and we use the same password over and over again on multiple sites, exposing us to a potential chain reaction of account intrusions if it is uncovered.

One way to address this problem is to use a password generator—the idea is that all you have to remember is a single, good, strong password, and the password generator will spit out a random string of characters to be used as a password on a particular site. This generated password is hard for an attacker to guess, and hard for them to “crack” with password-attacking software. You’re not supposed to remember or even care what the actual password is: you just remember the master password. And if one of the sites you have an account with is compromised, it may suck for you with respect to your sensitive information on that site, but because the generated password is unique to the site, you’re safe from having it used against you on other sites where you have accounts.

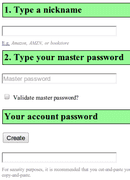

The password generator I use is called Oplop. It’s just a web site, so you visit it in your browser; there’s nothing to install. There are two fields to enter—a nickname, and the master password. The nickname is any name you want to identify the site or service for which you need a password. After you enter a nickname and your master password, you click the “Create” button, and an unguessable password is generated for you in the field below the button. Enter that password into the site that’s asking you for a password, and you’re all done. The next time you visit the site and need to enter your password, you repeat the process exactly to get the same unique password that’s just for that site.

There are a few tips and tricks to using Oplop successfully. The nickname is just a label that you remember to refer to the site you need a password for, but if it is different by even one character, an entirely different password will be generated. So it’s important to be consistent, and ideally use a simple convention so that you enter the label the same way every time. I’ve chosen a convention of using all-lowercase and no non-alphanumeric characters, and the domain name of the site, minus the top-level domain (the .com or .org, etc.). For example, if I’m on amazon.com, I’ll use “amazon” (without the quotes) for the nickname. If I was visiting a site with the domain name “Cat-Pics-123.net”, I’d use “catpics123” for the nickname. Whatever your convention for nicknames, it should be simple and you should use it consistently.

Your master password should be a good one—fairly long and hard to guess—since it is the key to the kingdom. Security researchers often praise the idea of “passphrase,” a sentence instead of a single word. These can often be easier to remember and are just as strong if not stronger than shorter, gobbledygook passwords, even if the passphrase is composed of simple words. A four or five word sentence, separated with spaces, should suffice, although longer passphrases are even better. In any case, use care when entering your master password into Oplop. By default, it doesn’t do any checking, so, like in the case of the nickname, a single character’s difference means a whole different generated password. You can optionally click on the checkbox “Validate master password?”, which adds an additional password field for you to re-enter your master password, providing a simple check that might catch a typo in the first field.

The final tip is to cut-and-paste the generated password out of its field instead of copy-and-paste. It’s not so much a tip per se because Oplop recommends that you do this right on the page, but it’s important enough to reiterate. Doing it this way prevents someone from snooping over your shoulder, or if you are careless and leave the Oplop page open untentionally on a shared computer.

You might have stopped short at the notion of a web-based password generator. Isn’t it insecure to trust a web site to generate a password for you? The answer is, you are only actually interacting with your browser—there is no network activity taking place when you generate a password with Oplop. That is because the entire Oplop program is just HTML and JavaScript loaded in your browser, and it is your browser on your local computer that takes the nickname and master password, performs the cryptographic magic on them, and outputs the generated password. In fact, Oplop works offline just as well. You can test it by visiting the site and bookmarking it on your iPhone or Android, deleting the browser window, putting the phone in airplane mode, then loading Oplop from the bookmark. It works just the same as if you were connected to the internet.

The browser-centric nature of Oplop gets to another key concept about it—there’s nothing to install. In fact, it is essentially already installed on any internet-enabled device with a JavaScript-enabled browser. There’s no central database of account names and generated passwords, like you might expect, and which password generators like 1Password and Password Gorilla are built around. These programs work similarly to Oplop in the end result, but their central database presents a user experience problem—it needs to be shared among the computers you want to use the program on. This can make it difficult to retrieve a password if you are on your friend’s laptop or a PC at an internet café. Not only do you have to install the password generator software itself, if you are allowed to by policy of the computer’s owner or manager, you have to synchronize the central database with the computer. By simply eschewing the notion of storing account names and passwords, Oplop provides a universally-accessible password management tool. Those unique generated passwords are just ephemera, the results of combining the secret you keep in your head (your master password), the site nicknames, and a cryptographic function in your computer. Even the notion of the “master password” is turned on its head—it’s not unlocking some database of passwords, it’s combined with the nickname to make a cryptographic hash, the bits of which make up the final generated password. You could start using a different master password at any time, which essentially would invalidate any extant passwords generated with the old one (you still would have to manually go in and update each password on each site, though).

There are other approaches to securing your passwords, including writing them down. In fact, if you have trouble remembering strong passwords or passphrases of sufficient length, you might consider writing down your Oplop master password on a slip of paper you keep in your wallet.

Oplop is not perfect—it outputs a fixed style of generated passwords that may not meet the password criteria for various sites and services, which require certain lengths, or a certain mix of characters. It also doesn't address the need of strong, crypotgraphically-secure storage of ad-hoc information such as credit card numbers and other sensitive account information, which are often stored alongside passwords and account names in more traditional central database-style password generator programs. But this is by design and not a failing of Oplop. I continue to use Password Gorilla for this scenario, especially for protecting financial information. Also, there are certain threats Oplop can’t protect against, And it’s worth understanding what they are before you start using it.

Oplop addresses the proliferation of passwords across multiple web site accounts, is simple to use, and works everywhere there’s a browser. So stop using “letmein” for all your web site accounts—you’d be much better off plugging that in to Oplop as your master password. But don’t. Use a better one.